The sight of audio cables sprouting from students’ ears has become a ubiquitous sight within schools around the world. Despite frequent pushback from teachers and parents, many students swear by their ear buds, vehemently arguing that music helps them focus, learn, and remember.

It turns out, they may not be entirely wrong.

The underlying concept to help make sense of the ‘music while studying’ issue is called Stochastic Resonance. Put simply, stochastic resonance suggests that injecting noise into a system can actually enhance the function of that system.

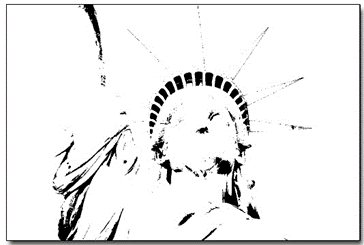

As a simple example, take a look at the image below:

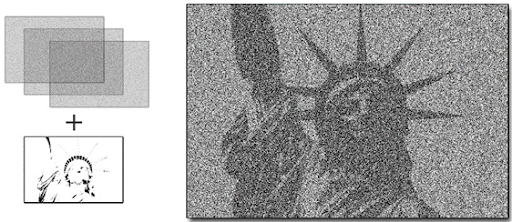

I’m guessing you can make out Lady Liberty, but it’s not easy – she’s a bit faint, a bit blurry, a bit blown out. Now, let’s add some noise to this image. In this case, the noise we’ll employ is that chaotic ‘ant-race’ static that used to pop up on old television sets when flipping between stations. Watch what happens:

Adding noise increased contrast, enhanced detail, deepened tone – in other words, it made the image easier to discern. But don’t get too excited – watch what happens when we add more noise:

With too much noise, the signal degrades once more.

So, what does any of this have to do with music and learning?

“When utilized correctly, music can resonate throughout and serve as random noise within attention networks of the brain, enhance their function, and actually make it easier to perceive and sustain focus on incoming information.”

Music can serve as a source of stochastic resonance inside the brain. When utilized correctly, music can resonate throughout and serve as random noise within attention networks of the brain, enhance their function, and actually make it easier to perceive and sustain focus on incoming information.

For this process to work, however, there is one very important caveat: the music must remain noise. In other words, it must be predictable enough that it does not explicitly grab and focus attention. This does not mean the music need be monotonous or boring – it need only be highly predictable to the listener.

For instance, I have a Best of Hall and Oates album which I have listened to hundreds of times. As such, when I hit play and simply let that album play out, the music quickly becomes noise and can enhance my ability to focus on other tasks. However, when I put my music app onto shuffle and every 3 or 4 minutes a new, unpredictable song pops on, then the music becomes a signal (not noise), draws my attention, and harms my ability to focus on other tasks.

There is one additional point worth mentioning: every person has a different threshold. Whereas some individuals may require a lot of noise to benefit from stochastic resonance, others need very little or none at all. As such, the utilization of music to enhance attention must be done at the individual (rather than group) level: there is no one-size-fits-all model.

Furthermore, every person’s threshold changes situation-to-situation. As such, individuals must be aware of their unique state within differing contexts, be aware when music is helping or distracting, and adapt their behaviors accordingly: there is no one-size-fits-all-the-time model.

So, what does this mean for us in schools?

First, it’s worth listening to our students. When some of them say they learn better with music, they might be telling us the truth. In fact, most students who require stochastic resonance to focus will telegraph it – they will be those students whose leg continuously bobbles up and down during class. Think about it: those kids aren’t paying attention to their jittery leg; they are simply trying to add noise (in this case, kinetic noise) to their system to help them stay focused on the lesson. If you see the leg moving, just wait for them to ask for music!

Second, if we’re going to allow music in our class, it must be done on a student by student basis. This is the only way to ensure those who will struggle with too much noise aren’t unduly impeded by our playing music to the entire class.

“It’s worth teaching our students this mechanism. Once they know why music works, then they must take agency over the process.”

Third, it’s worth teaching our students this mechanism. Once they know why music works, then they must take agency over the process.

In my class I have a one-strike rule. After teaching my students about stochastic resonance, I explain that if I see anyone dancing to a song, singing some lyrics, or frequently changing songs on their device – the music is done. With knowledge comes responsibility, and part of that responsibility is to use the music right. The moment it becomes a distraction, the party is over.