Reading is a complex cognitive task. This, coupled by the current reading wars, can leave the best educators left wondering what to do. Co-departmental RTI teams are key to creating cohesion to this chaos. Using multiple data points, experiences, and backgrounds, this team can create just the right prescription for struggling readers.

The RTI Table: Where it begins

Have you ever left an RTI meeting confused, frustrated, or wondering how to help your student? Effective intervention begins when teachers from each department gather with data specific to each student. Special education teachers attend with progress monitoring data and psychological evaluation reports. EL teachers bring ILP plans and WIDA data. Title I teachers bring benchmark data, selection criteria, and anecdotal notes. The instructional coach and/or reading specialist leads the meeting, but everyone is a stakeholder.

Struggling readers demonstrate patterns of strengths and weaknesses relative to the five pillars of reading. Using chart paper and Google sheets, the team creates a strategic reading plan that targets the specific deficits of each reader. This picture moves RTI teams away from grouping students based solely on a lexile or Fountas and Pinnell score. Instead, this team dives into the core of where a student is struggling.

Moving beyond the reading level: A collaborative approach

Step one begins with looking at students who are most at-risk according to diagnostic data. In this example, English Learners students are analyzed first using the questions below as a guide.

- Do WIDA scores align with the benchmark score?

- What areas of weakness are presented on the diagnostic?

- What intervention would best meet ILP goals?

The group continues with analysis of special education students. Special education teachers provide data from the psychological evaluation reports to determine areas of strength and weakness using these guiding questions:

- What are the student’s short-term memory scores?

- What are the student’s long-term retrieval scores?

- What are the student’s visual processing scores?

- What are the student’s auditory processing scores

- What are the student’s processing speed scores?

- What are the student’s crystallized knowledge (background knowledge) and fluid reasoning scores?

Next, the group discusses how diagnostic data aligns with patterns of strengths of weaknesses. The reading specialist continues the discussion with guided questions such as:

- How does the diagnostic score for phonics align to the student’s auditory processing score?

- What do the benchmark scores for literature or nonfiction text show?

- Do processing scores correlate with diagnostic data?

- What scaffolding strategies can we use to improve this score?

All discussion points from these questions are written on chart paper to keep conversations focused to specific students. The team examines data points for correlations. For example, when students have processing speed deficits but strong virtual processing scores, modeling think alouds that the student repeats with a partner, providing scaffolds that include sequencing, and creating visual representations, like drawing pictures of the content on a whiteboard, are high leverage practices that support the students’ strengths and weaknesses.

These discussions continue for Title I students. The power occurs when the team makes discoveries about students by combining interdepartmental data. For example, if a student with short term memory issues is shown how to use notes as a scaffold for remembering events in the text, it increases the chances of success. Think alouds, elbow partners, and layered approaches like the think-pair-shares give students with memory deficits the support to demonstrate comprehension. The RTI team then makes a plan to train support staff how to scaffold instruction based on specific patterns of strengths and weaknesses.

Why the running record is such a valuable resource

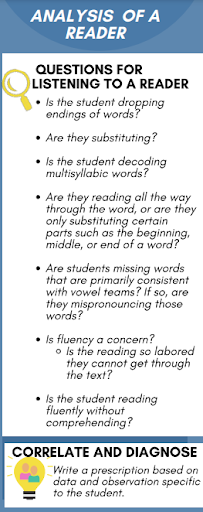

Struggling readers often show what my colleague, and school psychologist, refers to as a scatter plot. One data point may show proficiency phonemic awareness, while a level 1 screener shows the student still has not mastered certain concepts. When armed with multiple data points, a running record becomes a vital tool for the team to plan tiered interventions. When listening and observing a student read, interventionist should note the following:

These observations reveal a lot about a reader, and the team member knows what to look for during this observation because they have thoroughly analyzed multiple data points. After completing the running record, we begin by making two intervention group categories for struggling readers: Decoding or comprehension. This way, the team has intentionally listened to the student’s reading and analyzes errors to learn how it correlates with other data points.

In the words of Mike Mattos, this is where the rubber meets the road. The team creates targeted intervention plans for each group. First, the decoding group is separated by students who substitute multisyllabic words, drop endings, and are stuck at the transitional reading level. This tier 3 group will involve teacher syllabication methods, decoldables, and application of syllabication with running records. Meanwhile, students who cannot identify vowel teams, cannot blend sounds, or drop endings of words will be placed in a comprehensive Orton-Gillingham group.

Next, the team divides students into interventions targeting comprehension skills. Low comprehension scores outside of special education indicate a lack of vocabulary development or background knowledge. Background knowledge is a key predictor to reading comprehension. Without it, students often have weak vocabularies and difficulty accessing increasingly complex text. Our district uses i-READY. Students who score poorly on the nonfiction portion of the diagnostic will be placed in a group that builds background knowledge and explicitly teaches close reading skills. Students with low vocabulary skills will be placed in an intervention that utilizes best practices for vocabulary instruction. However, creating a strategic plan for struggling readers doesn’t end once specific tier 3 interventions are designed.

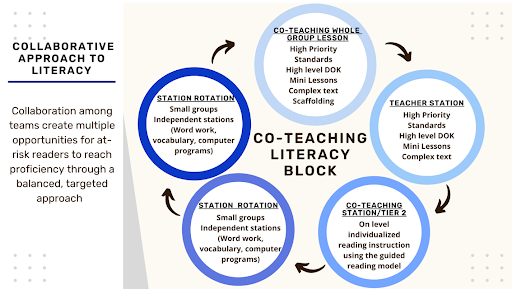

When departments work together, at-risk students receive multiple exposures to increase reading skills without using a one-size fits all program or focusing on a single skill.

Co-Teaching and combing tier 1 and 2 for holistic approach

When individual departments work as a team, silos become cohesive groups. After establishing tier 3 groups, the RTI team uses this data to design high leverage co-teaching practices within the 90-minute literacy block. General education and special education teachers work together with grade level standards.

For tier 1, this team designs lessons with scaffolded support to ensure all students have the opportunity to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate grade level text with the appropriate scaffold. This may include sentence starters, think alouds, additional teacher modeling, videos, or other high leverage practices. At the general education teacher station, scaffolds are put in place so at-risk readers can recognize the changes in plot, emergent themes, character motivations, and reasons for the author’s choice in point. The goal is for all students to relate, to think, and to create ideas presented in text. This model allows all students to see friendships develop in novels such as Bridge to Terabithia, or recognize the plight of Peter Hatcher and his brother in Tales of the Fourth Grade Nothing. They are also taught to evaluate two sides of an argument in nonfiction text. While leveled readers have their place, the text is often not rich enough to enable older struggling readers the same opportunities to critically interact with text.

Next, tier 2 occurs through what we call the double dip. Students work in groups and attend 4-5 literacy stations per day. Stations such as the word work and i-Ready centers are independent. The special education teacher uses the guided reading approach for at-risk students at a separate station.

This tier 2 plan is designed by the RTI team. For example, students who receive Tier 3 Orton-Gillingham interventions are able to apply phonics skills and syllabication using leveled readers during the tier 2 station. Here, students have the opportunity to apply skills taught in isolation with leveled text they can access. These opportunities enable students to use vowel patterns to decode unfamiliar words outside of the systemic OG program while also receiving fluency practice. Students demonstrate success when they can apply knowledge and skills outside the systemic program.

Another example of tier 2 instruction led by a special education teacher within the literacy block addresses students who receive vocabulary or background knowledge building instruction during tier 3 interventions. In this case, students practice with a text slightly above their reading level to continue building reading comprehension skills. Our district uses Literacy Footprints, so double dips rely heavily on nonfiction text, which provides multiple opportunities to build background and vocabulary.

When departments work together, at-risk students receive multiple exposures to increase reading skills without using a one-size fits all program or focusing on a single skill. Instead, all teachers and support staff are equipped with the necessary to create strategies based on science that goes beyond a script and into the minds of their readers. It takes a lot of intentional planning and work on the forefront, but, in the end, everyone leaves with clarity and a strategic plan for support.